Another Country

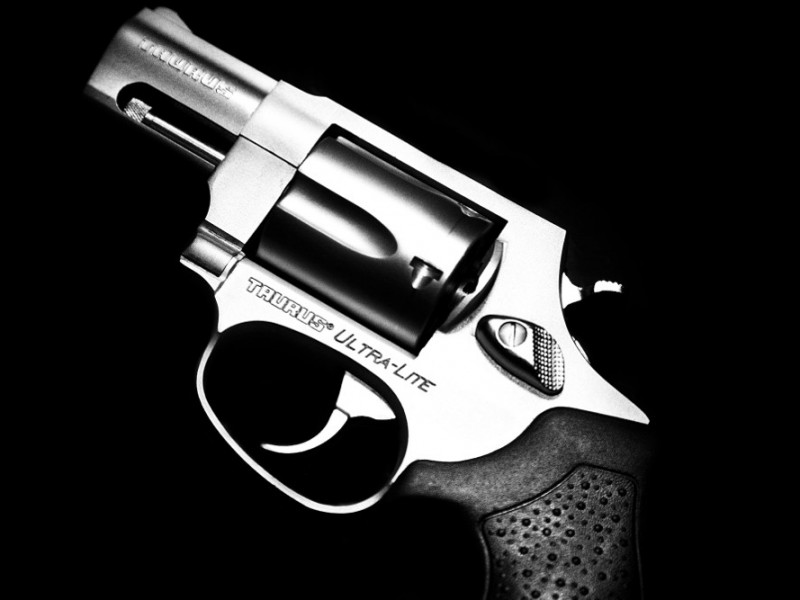

I’ve spent much of the last 25 years working in conflict zones. In 2010, in the midst of that work, I spent several weeks in the southwestern United States along the Mexican border. It was an experimental trip, and initially I did not have many expectations. However, I found something remarkable there, something that mattered to me within the context of the broader issues I had spent my career investigating – the guns, the racial tension, the economic disparity and the culture of surveillance seemed to be inextricably linked to the conflicts I had been witnessing around the world.

These themes captivated me, and after that first trip to the Southwest, I have been returning to America nearly every six months. However, I am not in pursuit of any particular story, but in an attempt to make sense of an ethos. I have been trying to get to the core of something about America, its spirit and ideals and the paradox that lies within them.

Racial discrimination is incredibly prevalent everywhere, in a way that is shocking for a European. It can be seen most clearly at the borders and in the criminal justice system, with its unending cycle of confrontations, arrests and detentions. I’ve spent considerable time with the police, and after the initial shock of the brutality, I’ve become even more taken with the complexity of the struggle: As brutal and degrading as the system is for those who are caught up in it, the police are also often reasonable, dedicated, and hardworking. Everyone feels trapped in a historical condition from which there is no easy escape. Although I began this work before the shootings and subsequent protests and violence in Ferguson, Missouri, I feel like I’m beginning to have an understanding of the dynamic at play there and in the other sites of protest that have emerged since.

The poor, and especially minorities and immigrants, legal or illegal, are constantly watched in America. The police, and the border control units, and various other pseudo-security forces, constantly patrol their neighborhoods to monitor them. Police cars, marked or undercover, approach conversations on street corners or at backyard barbecues. Social services agencies monitor children and teenagers. Benefits, food stamps, housing vouchers and medical care are tracked for signs of fraud. Young men are stopped and frisked on the street. Houses, or whole apartment buildings, are searched for suspects. Warrants are issued. Protective orders are handed down, banning one set of social interactions and mandating another, and then everyone involved is tracked for compliance. Drug tests are administered. Informants are everywhere. Probation, supervised release, conditions of bail – all are ordered by the courts and then enforced by a law enforcement system charged with checking for violations. Checkpoints are set up to search for drugs, or guns, or illegal aliens, or all of the above.

I also linked Guantanamo Bay, a place I have been photographing for many years, in an American context. In that regard, Guantanamo has begun to look like an extension of a domestic American idiom – albeit taken to an extreme – rather than an extraterritorial anomaly reserved for the other. Guantanamo is also the place where the link is made most explicit between America’s fears and aspirations at home, and its age of perpetual wars abroad.

Paolo Pellegrin’s project is part of the group exhibition Dalla via Emilia al mondo, curated by Diane Dufour, Elio Grazioli and Walter Guadagnini.